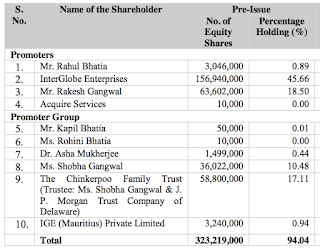

InterGlobe Aviation Limited is seeking to raise capital and accordingly, is filing its IPO in October 2015. There will be a fresh issue totaling Rs.12.722 b and an offer for sale of 26.112 m shares from the selling shareholders. Currently, there are 343.716 m shares issued and outstanding.

The promoters

The board

Managers

The objective of the issue

The objective of the fresh issue is explicit, while that of the offer for sale is implicit.

The story

InterGlobe Aviation operates IndiGo, India’s largest passenger airline, with a 37.4% market share of domestic passenger

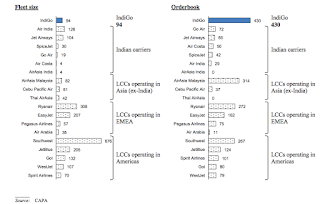

volume. IndiGo operates on a low-cost carrier (LCC) business model and focuses primarily on the domestic Indian air travel market. It primarily aims to maintain its cost advantage and a high frequency of flights - low fares, on-time flights and a hassle-free experience to passengers. IndiGo started operations in August 2006 with a single aircraft, and currently has a fleet of 97 aircraft all of which are Airbus A320.

IndiGo claims that its market share has increased to 33.9% in terms of passenger volume. It has the largest market share in terms of top 10 metro-to-metro, metro-to-non-metro and non-metro-to-non-metro routes. Its maintenance costs are the lowest among Indian airlines. Its fuel costs are also among the lowest. IndiGo is the only airline that has been consistently profitable over the past seven years. Its order book currently is the largest with 430 aircraft. Average age of its current fleet is only 3.7 years. IndiGo's EBITDAR margins are the highest at 19.8%.

Extract from the prospectus:

One reason for IndiGo to remain profitable is that it uses only one type of aircraft (Airbus A320) with a single type of airframe and engine, which reduces its operating, maintenance and crew training costs; it also facilitates fuel efficiency.

IndiGo is strictly a no-frills product airline: It offers a

single class of economy service, which allows for the maximum seating capacity of 180

seats. Unlike most full-service carriers, it does not offer a frequent flyer program, free lounges or include

food and beverages in its ticket price for non-corporate passengers.

Revenues increased from Rs.38 b in 2011 to Rs.139 b in 2015.

So far, it's been consistently profitable:

As of 30 June 2015, IndiGo had long term debt of Rs.35 b mainly aircraft related, and cash of Rs.22 b. There wasn't any short term debt. However, it remains to be seen how non-cancellable operating leases have been dealt with in the books. Any such commitment is a form of debt.

The airline has been generating free cash flows:

Just that those dividend payouts appear to be special and intentionally managed.

Who are going to make money

There are others who too get to make money

What can go wrong

While the majority is gung-ho about this IPO party, it is worth knowing the risks highlighted in its Red Herring Prospectus.

There are several legal cases pending against the company amounting to at least Rs.9,642 m. Of course, the final outcome depends upon the probability of ruling. The present value of the probable amounts will affect its value.

The prospectus rightly notes that airline business is a low margin and high operating leverage business. Especially, aircraft lease and acquisition costs and engineering and maintenance costs cannot be postponed. The industry is laden with intense price competition.

Aircraft fuel costs represent the single most significant cost item for an airline accounting for almost half of its total operating costs. Fuel costs vary in terms of fluctuations both in the international oil prices and in the US dollars exchange rates. For an airline, the ability to pass on increases in fuel costs to the customers is limited. Whether is worthwhile to hedge oil prices risks is open to debate.

IndiGo has plans to expand its current routes and also to other tier II and III cities in India, and later to look for expansion of routes in South East Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. How far it will be able to replicate its LCC model is the moot question.

It has agreed to purchase a total of 430 Airbus aircraft under its 2011 and 2015 purchase agreements. This right is generally assigned to a third party lessor, and the company takes delivery of the aircraft under a sale-and-lease-back agreement. If the business faces adverse conditions or if the lessor defaults, the financing of aircraft would be in trouble. This will have the biggest impact on its ability to continue as a going concern.

Extract from the prospectus:

The company is making some interesting statements about transactions with its related parties. Check out the risk factors # 4 in the prospectus. It is almost hinting that these transactions were not on an arm's length basis and might have adverse effect on its cash flows.

The aircraft leasing and financing arrangements have restrictive covenants, breach of which might adversely affect its survival.

The company has acknowledged that there are lapses in its internal controls, and the auditors have qualified on the delay in dealing with certain statutory dues. This also speaks about the quality of management.

IndiGo has also acknowledged that it is seeking an implied valuation for its equity in excess of the international LCCs such as Air Asia, Cebu Pacific, Ryanair, Southwest Airlines, Spirit Airlines and Wizz Air. Higher issue price will adversely impact the return on investment for the IPO subscribers.

The company has been subjected to an ongoing investigation regarding competition and cartelization.

The managers have intentionally turned book value of equity to negative by paying out special dividends to the existing shareholders. This speaks about the intention of both managers and selling shareholders.

While revenues are mostly earned in Rupees, a significant portion of costs including leasing and financing, engineering and maintenance and aircraft fuel are incurred in US dollars. There is a clear mismatch between the cash flows, which is rather difficult to fix unless the company uses derivatives to hedge its foreign currency exposure.

There is a likely dilution in equity due to 1,111,819 shares granted through employee stock options at an exercise price of Rs.10 per option. In addition, 578,746 options are proposed to be granted at an exercise price of Rs.10 per option, and 2,528,928 options are proposed to be granted at an exercise price per option equal to the issue price.

We can get to know more of the risks (there are 68 in number) highlighted in the prospectus. Check them out.

IPOs are diced against investors

In addition to these, there are some obvious risks for investors in any IPO. Here are a few sellers who know more about the business selling shares to a large number of buyers who know much less (or mostly nothing at all) about the business, and these sellers have the option to choose the time to sell the shares to buyers having no such option and at a price implicitly chosen buy the sellers.

What do we expect? Unless the sellers are dumb, they would choose a rising market and price the shares so that the collections are the highest. IPO is indeed a very good mechanism for promoters to get rich quickly. The dice is rolled against the investors; so it is always the buyers beware. There is no point in blaming the sellers. It is never a fair game.

The kind of profits that are going to be made by the promoters can be noted from this:

The basis for issue price

For sellers, the determination of issue price is easy for obvious reasons, nevertheless it is noted in the prospectus in a manner that is to be noted. However, it will do well for investors to know that due to fresh issue of shares and through employee stock options, there will be dilution in both earnings per share and return on equity in the coming years.

It looks like IndiGo is better managed compared to any other airlines in India.

Extract from the prospectus:

I don't really like EBITDA as it is dangerous to assume that capex requirements are offset by depreciation and amortization.

Here's EBITDAR for airlines extracted from the prospectus:

No wonder then that IndiGo is seeking higher valuation compared to its peers.

To be or not to be

That is the question. I am not considering this IPO for two reasons: Airline is inherently a bad business. I am as biased as one can be towards an IPO, that is any IPO. I like to play the game my way.

You have your prerogative too. You can ask whether IndiGo is worth Rs.32 b.