Airbnb recently raised $1.5 b from private equity, valuing its total equity at $25.5 b. It is expecting revenues of $0.9 b, compared to Hilton's revenues of $11.5 b and Marriott's $14.8 b. Clearly, the investors are seeing something in Airbnb that they don't see in Hilton and Marriott. That is the growth in the future.

We know that equity valuation is all about estimating future cash flows and looking at their present value. Usually, the expected return for private equity is quite high compared to the actual cost of equity of the invested firm. That is why, they look for the platforms where cash flows are likely to be much higher than others. The higher the growth rate in future, the higher the investment from private equity.

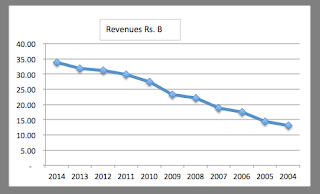

And we also know that all growth does not create value. For growth to create value, it has to reinvest capital efficiently, which is measured by return on capital for the firm and return on equity for the equity. Airbnb's expected annual growth rate in the next few years is 90%, compared to Hilton's 9% and Marriott's 8%. This has made Airbnb a natural playground for the private equity. The investors have valued Hilton at $27 b, and Marriott at $20 b. These hotels had operating margins of 15.93% and 8.4% respectively for 2014. Hilton and Marriott are also the biggest hotel companies in the Fortune 500 list after Las Vegas Sands.

Both Hilton and Marriott were started centuries back, while Airbnb is less than ten years old. Of course, that does not mean much considering the disruptive transformation that has been taking place over the globe. Brian Chesky is a cool guy, and sure, he has plans to disrupt (that's cool these days) the industry.

Both Hilton and Marriott were started centuries back, while Airbnb is less than ten years old. Of course, that does not mean much considering the disruptive transformation that has been taking place over the globe. Brian Chesky is a cool guy, and sure, he has plans to disrupt (that's cool these days) the industry.

To justify an equity value of $25.5 b, what should be the revenues, operating margin, and reinvestment for Airbnb in its high-growth years, and then in perpetuity? Airbnb itself has estimates of $10 b revenues by 2020 and profit visibility by that time, which means it is not going to be profitable for another 5 years. That it is not going to payout any dividends soon is given. Industry average operating margin (12.50%), return on capital (7.50%), and sales-to-capital of 0.75 are not applicable to Airbnb considering the fact that it is not going to own properties, and consequently, would remain asset-light compared to the conventional hotel companies.

Airbnb has so far raised total equity capital of $2.3 b. I tried on a spreadsheet to bring $10 b revenues by 2020 (as estimated by the company) and $14 b by 2024. I also gave much higher return on capital (therefore, much lower reinvestment), and much higher operating margin than Hilton and Marriott. I assumed immediate profitability as opposed to the company's estimates of by 2020. I also maintained high return on capital and operating margin until perpetuity. Finally, my cost of capital estimates were modest (and nothing like the private equity). This was an attempt to give my best shot at getting close to $25 b in value. Heck, I got only $14.80 b. I have to do better the next time.

But wait, at $14.80 b of equity value, it is still a unicorn, is it not? May be I should work towards valuing the firm more realistically. Too bad, I can't, because it is way beyond me to estimate its future. I can play around with these stuff, and I like that, but, it is not my playground; my game is different.

Of course, the private equity knows it better, Chesky has already hinted about going public in about two years. At what rate the public market investors are going to be squeezed remains to be seen.

Airbnb has so far raised total equity capital of $2.3 b. I tried on a spreadsheet to bring $10 b revenues by 2020 (as estimated by the company) and $14 b by 2024. I also gave much higher return on capital (therefore, much lower reinvestment), and much higher operating margin than Hilton and Marriott. I assumed immediate profitability as opposed to the company's estimates of by 2020. I also maintained high return on capital and operating margin until perpetuity. Finally, my cost of capital estimates were modest (and nothing like the private equity). This was an attempt to give my best shot at getting close to $25 b in value. Heck, I got only $14.80 b. I have to do better the next time.

But wait, at $14.80 b of equity value, it is still a unicorn, is it not? May be I should work towards valuing the firm more realistically. Too bad, I can't, because it is way beyond me to estimate its future. I can play around with these stuff, and I like that, but, it is not my playground; my game is different.

Of course, the private equity knows it better, Chesky has already hinted about going public in about two years. At what rate the public market investors are going to be squeezed remains to be seen.